I published this on Linkedin and on the Facebook page....

Mineralogy is the core discipline of the geosciences; it is the subject that underpins our understanding of the Earth in the way that molecular biology underpins our understanding of the life sciences. This should be appreciated by all geoscientists and taught to the young people starting their studies in colleges and universities around the world. Convincing our colleagues of the importance of mineralogy and the cognate subjects of petrology and geochemistry is more important than ever as these core skills are being forgotten with the influx of newer and sexier technologies.

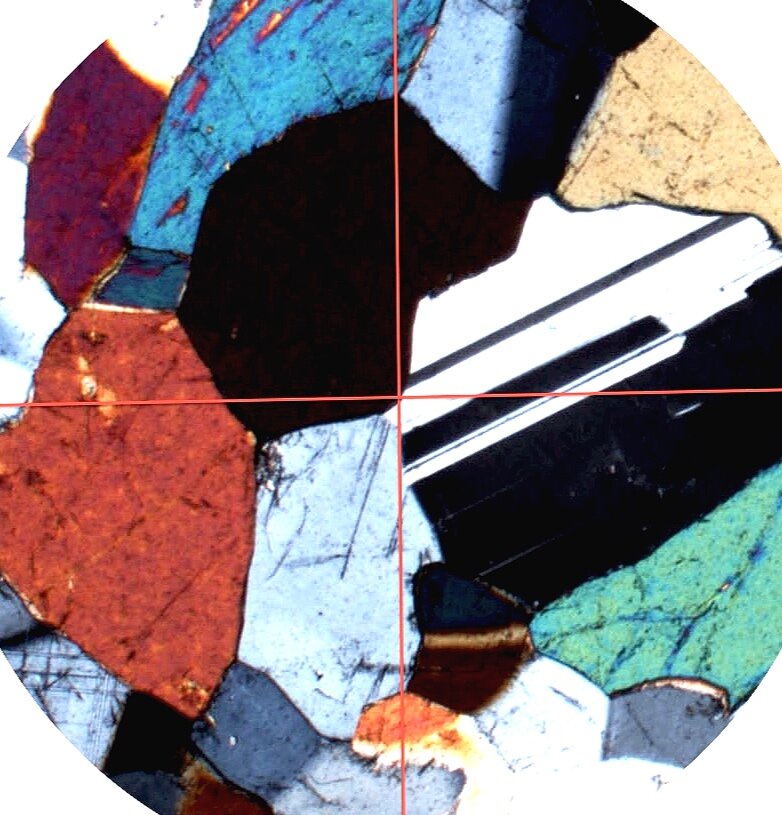

The detailed analysis of minerals by optical mineralogy in thin section and the micro-texture and structure are critical to understanding the origin and history of the rock. Hand specimen descriptions and detailed and accurate core logging in exploration are vital, but a wealth of extra information on alteration and paragenetic sequences can be obtained by the old practice of slicing a 30 micron section of rock and analysing it under a petrographic microscope.

This is even more vital where core logging is undertaken without hand lenses or by inexperienced core loggers. Ore targeting is based on mineralisation models, which in turn is based on the lithologies apparently logged. If this information is incorrect than many thousand of hours and dollars can be wasted. Several thin sections of representative lithologies can provide detailed and accurate information of mineralogies, metamorphism, alteration and paragenetic history.

And do you really know where the gold/silver/copper/zinc/tin is those samples that you have assay values from? Is it related to an early pyrite or a paragenetically late phase one for instance? Finding this out via reflected light mineragraphy and electron microprobe analyses can save many thousands of $ when it comes to mine planning and processing. Automated mineralogy has its place but cannot tell you the story of the rock or any relational or textural information, and is limited by the data uploaded into the software operating system.

There is also a trend currently in this downturn to send sample overseas to get cheaper sections made, but cost commonly positively correlates with quality, and data obtained from such sections is limited and questionable, and much harder to obtain. If the section thickness is wrong, if the section is wedged, or if it is polished badly then mineral identification will be difficult, and photomicrographs will be misleading as colours can be incorrect. Cheaper thin sections are mass produced with no regard to the individual sample, and in these cases the grinding process often plucks out minerals, usually the ones of interest, and this can also result in tin and lanthanum contamination from the polishing media used. Deformation of the softer minerals can also occur. Sections like these cannot be used for any further analytical work such as electron microprobe or laser ablation on the polished section will be impossible. These analytical techniques cost hundreds to thousands of dollars, so why try and save a few dollars on the sample preparation?

We have less than a dozen excellent thin section technicians in Australia so why put them out of business for a sake of a few dollars? If they cease to operate then what happens when we need them again? It’s not a skill the younger generation are learning. Producing good quality thin sections is a dying art that we should all support, as petrography is a “core” data source in geology and should not be forgotten in amongst the mountaining pile of new and whizzy sounding technologies.